23 December 2019

Greetings from burnt-over Wat Buddha Dhamma, Wisemans Ferry, Australia

I have not been writing much in this blog over the last while, basically because there was not much to ‘ramble’ about. However, things changed quickly after the Rainy Season Retreat with the on-set of the Australian Bushfire season. Then it was so busy that I had little energy or time to write!

As some of you may know, Wat Buddha Dhamma is situated deep in the Dharug/Yengo National Park surrounded by dry eucalyptus bushland. When bush fires threaten we are advised to evacuate to a safer place. For Tuesday, November 12, the Fire Danger Level for NSW and Queensland was raised to ‘Catastrophic’, meaning all those in fire-prone areas should evacuate to safer areas. Since we were in no immediate danger (although the Park Ranger suggested otherwise), we initially did not think to leave. However, when we reconsidered the implications, some other options arose. We were in the path of an extensive, fast-moving, out-of-control fire some 45 km away (Gosper’s Mountain – the ‘mega fire’ now engulfing 470,000 ha) and would be spending the day shrouded in acrid smoke in temperatures approaching 40C.

After careful consideration it was decided that it might be a suitable day to take a picnic lunch and visit the local town to complete a few errands, then review the conditions in the early afternoon. By early afternoon fire conditions had deteriorated considerably with hot, windy conditions fanning existing fires and producing new ones. We thus decided to de-camp to an apartment made available to the Sangha in west Sydney to review conditions in the evening. By early evening fire conditions had truly become ‘catastrophic’ with 80 fires burning throughout the state, 15 at Emergency Level. Thus, at the invitation of our generous Vietnamese supporters, we remained overnight and were offered the next day’s meal. By morning, with a cool southerly weather change, fire conditions were considerably reduced and we made our way back to the Wat. As we approached Wisemans Ferry the northern horizon was covered in smoke, and from the ridge road we could see massive plumes of smoke billowing up from the vast swathes of burning National Park forests towards the northwest. Fortunately, the monastery property and surrounding area was not impacted by the fire, although the area was covered in a layer of ash, including finger-sized scorched leaves blown 40 km across the hills.

Our second evacuation occurred towards the end of November with a lightening strike at Three Mile Line on the Old Great North Road. Since we are at Ten Mile Hollow on the Old Great North Road we did not appear to be threatened. However, the Fire Service was concerned that the fire would cut off our access road and advised to evacuate. With telephone calls coming in, a siren-wailing helicopter hovering overhead and a visit by fire personnel, we decided to depart for the lodging in west Sydney to appease the officials. We returned to the monastery the following day and met an official who said all was good and that they would begin a controlled burn soon to contain the fire some two miles from us. However, this was delayed and high winds on Monday forced the fire over the proposed containment line to within 5 km of us. On Tuesday morning we were warned that the fire was slowly approaching but that the winds were directing the main fire-front away from us towards the east. However, by late afternoon we were notified of potential ’ember attack’ and, collecting our valuable possessions, all assembled in the vicinity of the kitchen/office in preparation. Having donned protective clothing, set out fire hoses, filled gutters with water and cleared extra-wide fire-breaks, we sat down for refreshments as increasingly dense smoke billowed over the ridge. Just as we were preparing to retire to our ‘safe house’ – an earthen building stocked with water and medical supplies, and with ample clear space – the first flames crept over the ridge to the south-east. It was still about 600 meters distance and on the opposite side of the road from the monastery so did not appear overly-threatening – night was approaching, the winds were dying down and the fire was moving downhill. We casually watched the flames creeping along the ridge when three helicopters suddenly flew overhead and landed in the large field nearby telling us to depart immediately leaving all belongings behind. I was not keen to leave my passport and necessary items so suggested that we could take our belongings and drive out the back route away from the fire. This was agreed and we quickly loaded our things and departed in two vehicles, remembering to take the chain saw and bolt cutters (in case the gates were locked).

We set off briskly but, upon making our first right hand turn through the clearing under the power lines, observed that the fire front had crested the ridge and was halfway down the nearby slope. We had not realized that the westerly winds had forced the fire-front past our position towards the east. We moved off more briskly on the eastward track and several more curves directed us straight towards a steep slope where the flames were being whipped 40 meters over the ridge tree tops. We descended the narrow track winding along a rocky gorge over deeply rutted washouts before the track leveled out and the bush thickened through the gulley. However, in the lower reaches of the valley the smoke began to thicken and another curve brought us to within 150 m of a ribbon of fire creeping down the slope. For a moment I thought that the fire may be in front of us but we had little choice but to continue forward. We sped ahead through thickening smoke and darkness only to run into a fallen tree across the track. Fortunately we had the chain saw and were able to quickly clear the path as the red glow flickered over our right shoulders.

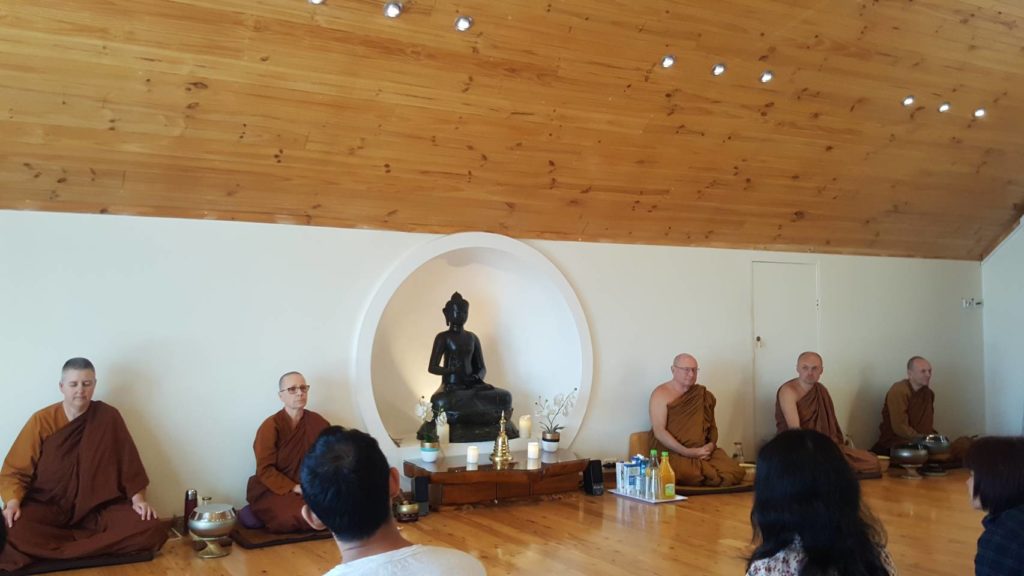

Shortly we arrived at the track along Mangrove Creek, fortunately recently ploughed, and turned away from the encroaching fire front along an increasingly well-maintained gravel track, then up the opposite slope through Dubbo Gulley to Upper Mangrove village. While we waited to find a place to stay, a Rural Fire Service vehicle arrived to confirm that we had all managed to evacuate and report on the advance of the fire. After a short discussion, the six of us were very warmly received by the residents of Aloka Meditation Centre where we resided for two nights. Then our Vietnamese supporters took us to a house in west Sydney and the next day we travelled to Santi Forest Monastery where Sisters Jitindriya and Jayasara generously invited us to make use of the much-appreciated quiet and solitude. For nearly a week we had little news of the condition of the monastery except that dramatic footage on national television of my cottage blazing and helicopters water-bombing the Sala sent panic through our lay community and an avalanche of text messages expressing concern (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-04/one-home-has-been-engulfed-by-the-three-mile-fire/11767160).

Finally one of our fireman supporters managed to access the property and reported that the buildings were 80% intact! We have since made an inspection to assess the damage. Fortunately, all main buildings survived, and the only loss were three monk’s huts [including the iconic ‘Ayya Khema’ Rock Kuti], plus several caravans, wood piles, toilets and water tanks. Unfortunately, some of the water pipes were damaged and water supply has been disrupted. Also unfortunately, most of the forest has been completely devastated, in some places leaving only charred sticks standing.

The following weekend many supporters braved the difficult conditions of trees on roads, smouldering stumps, charred forest and cold showers to assist in an initial clean-up. A week of chain-sawing and plumbing work has now seen most tracks cleared and water restored to the monk’s area.

We are most grateful to the Rural Fire Service who helped protect some of the buildings, to all those who generously housed and supported us during this chaotic and distressing time and all the open-hearted people who expressed their well wishes and contributed to expenses and the re-building fund. The smell of burnt wood and sight of blackened forest still lingers about the property (probably for months), however, we are heartened by the dawn chorus of cackling kookaburras, the sighting of our local wallabies, wombats and goanas, as well as increasing numbers of birdlife.

While all situations in life can be a source of contemplating impermanence, it is extreme times like this that bring the truth of impermanence directly into our minds. Most often we contemplate impermanence while in a relatively safe and secure environment such that this contemplation is usually in the abstract – yes, things are impermanent but not me. Suddenly, in the blink of an eye, your world can be turned upside down and, if you have not seriously understood impermanence, you can be over-whelmed with suffering at all levels of being at once.

One of the huts which burned down was the Mahathera cottage where I had been staying. Initially, someone who saw the television images told us that it was the Sangha House which had burned down. This news was saddening, but when we established that actually it was my lodging that had burned down, I had to choke back some personal tragedy for the belongings I left behind!

I am still getting used to the situation where people wish to offer me something and my first thought is that I already have it. Then I realize that actually, it is now burnt up in my former lodging! Interestingly, upon reflection, it was not the things themselves that were the source of sorrow but rather the sense of me and mine which those things represented. There were things associated with my personal history – a fossil from the rocky coast of Portugal; there were things that relieved some personal pains – special circulation-stimulating socks for feet pain; there was my selection of favourite teas, etc. In one sense, of course, this can be positive as a means of liberation from identity. Yet, while nothing there was irreplaceable, there is still sorrow at any loss of selfness, and a form of dislocation before another sense of (new) selfness is re-established – hopefully more in tune with continuous impermanence.

The Buddha often encouraged the contemplation of impermanence as one of the direct means to liberation. Other times he extended this to include the contemplation of dukkha since impermanence is always unpleasant for the sense of selfness, which is founded upon stability and need for security. This can lead to an increased understanding of ‘anatta’, no stable self, in that, what is impermanent and dukkha is, of course, not a stable self.

We blindly assume that we are in control of our life. However, the ultimate truth is that our life is controlled by the elements of earth, fire, water and air. While we may rant and curse them when they are extreme, we should reflect that actually these elements were here long before us. They are just impersonally following their nature – we are the ones who are in the way.

Wishing you all an insightful New Year and the peace of realization.

Additional pictures of WBD after the fire: WBD Bushfire 2019

More posts my Ajahn Tiradhammo at: Tiradhammo’s Ramblings